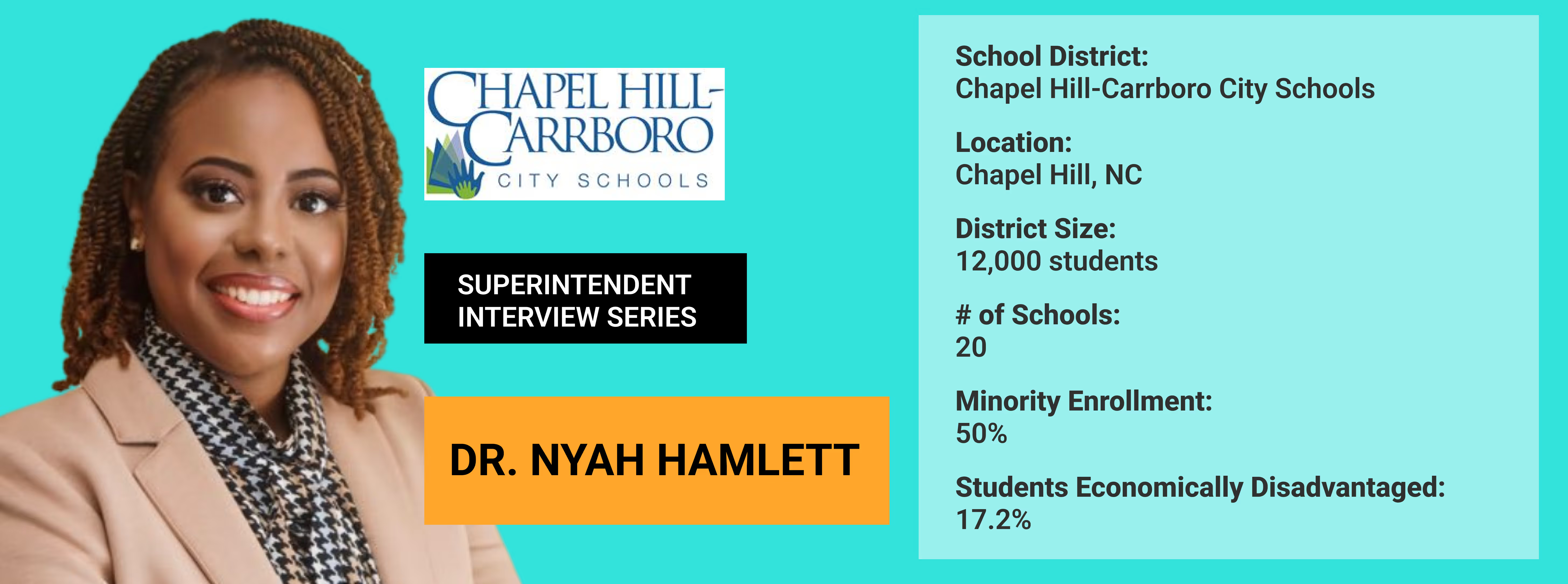

The Importance of Mental Health and Student & Family Engagement: A conversation with Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools Superintendent Dr. Nyah Hamlett

For this special edition of our Superintendent Interview Series, Daybreak’s Director of Partnerships and K-12 District Consultant and former Chief of Student Support at Boston Public Schools, Jillian Kelton, spoke with several Superintendents at the annual Superintendent Collaborative meeting held on June 26-28, 2024. These interviews cover topics and trends affecting these Superintendent’s school communities such as student mental health, chronic absenteeism, academic outcomes, and more. Our goal is to capture different voices and perspectives on the challenges facing our schools today.

Dr. Nyah Hamlett stepped into her role as Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools (CHCCS) Superintendent in January 2021, moving to North Carolina from Virginia, where she was chief of staff for Loudoun County Public Schools. Today, Dr. Hamlett serves around 12,000 students and 2,000 employees across 20 schools.

The district, considered to be one of the best in the nation, consistently ranks at the top of the state in student performance. But the job is more than a numbers game for Dr. Hamlett, who joined CHCCS in the midst of the global health crisis. The first two graduation ceremonies she participated in as Superintendent, “[there was] no joy in those students' eyes, but I've seen growth over the years. This cohort, this class of 2024, I saw a huge difference,” Dr. Hamlett says. “Just the eye contact, the firm handshakes, the dancing across the stage.”

It’s this heartfelt personal connection, coupled with an unwavering dedication to student-centered problem-solving, that embodies Dr Hamlett’s commitment to the district's core values of engagement, social justice action, wellness and joy.

Giving Students a Voice

One of the biggest challenges students faced as they returned to the classroom after remote learning was a sense of belonging, Dr. Hamlett says. To figure out what students needed to feel good about school, she asked them herself, setting up the district’s Student Equity and Empathy Ambassador Program. Today, more than 40 high school students consult with Dr. Hamlett and her team around policy and programs, in addition to providing a sounding board for student needs.

In one early meeting, Dr. Hamlett asked the group whether the board should continue to engage in the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with local law enforcement and continue to employ School Resource Officers. Her students flipped the question, saying, “You really should be asking us what it is that we need to feel safe and be safe in schools, not whether we need armed police officers in our schools.” Instead, students said they wanted to be able to “connect with each other and connect with the adults,” which just wasn’t happening at the time.

“The bottom line is, I think students are becoming more and more comfortable with identifying what their needs are. And it's very rarely centered around the things that we, as adults, think that they need,” Dr. Hamlett says. That can look like anything from student wellness days to a revision of grading policies or hiring more mental health specialists.

Prioritizing School-Based Mental Health Services

The Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools District is well-resourced, which means Dr. Hamlett can focus on building and/or improving systems and structures, instead of constantly reallocating human resources to meet student needs; although she is finding that the district is not immune to the same budget challenges that many districts across the country are facing. “One of the priorities of our strategic plan is creating a culture of safety and wellness. And that's not just for students, but also for staff,” Dr. Hamlett says. “I'm a huge proponent of school-based mental health services. Something we really need, and something we’re starting to work on, is helping folks understand that … SEL and school-based mental health are not the same thing.”

Every CHCCS school has a school psychologist, a school social worker, a school nurse, and school counselors. In some districts that level of staffing would be spread over three or four schools, Dr. Hamlett says. But in a post-pandemic world, the demand for support is higher than ever. “The climate has changed and we are having to do things differently,” she says. “The behaviors of our elementary and middle school students have increased significantly, and I'm finding that our social workers and our student services folks are having to really support teachers who think [the solution is] a special ed referral.”

CHCCS’ mental health specialists have observed that more students are living with depression, severe depression and anxiety, which is directly connected to school refusal and chronic absenteeism, Dr. Hamlett says. In a previous role, she set up a Social Emotional Support Services Program, where mental health teams helped train teachers. “It wasn't the typical things that you would think that teachers would want or need professional development on, but it was helping them to understand some of the trauma and experiences that students were coming with.” For CHCCS, there’s an opportunity to fill teachers' toolkits with restorative practices so that they are better able to provide the support students need in a tier one environment.

The Importance of Family Engagement

Dr. Hamlett takes an in-person approach to preventing absenteeism, and it doesn’t require a suit and heels. “We try to do things differently. Rather than inviting parents into a meeting or some type of event within the four walls of the school, we try outreach,” Dr. Hamlett says. She regularly heads off on Superintendent Neighborhood Walk and Talks to check in with students and families on basketball courts, in clubhouses and at housing estates, because “what's top of mind for one community is very different than what's top of mind for a community that's just five minutes down the road.”

Also on the agenda is a disconnect between a mostly white student services staff and BIPOC students. “There's a very clear lack of trust from our communities of color, our newcomer families, our Black families,” Dr. Hamlett says, but it’s not a policy issue. “It's [already] hard to find mental health specialists, or school social workers, or psychologists for the pay that they get in a public school system in North Carolina.” Instead, Dr. Hamlett believes the solution to a more diverse support staff is already in the room. “We’ve really looked into what it looks like to ‘grow our own,’” she says, including providing employees of color a chance to work towards certifications such as to become a certified teacher or obtain a certification as a licensed clinical social worker LCSW.

“From a family and community engagement standpoint, we really try, whether it's a big decision that we're making in our district … or whether it's just what's top of mind for a community right now, we just go in to their neighborhoods, where they are most comfortable and have conversations with folks,” Dr. Hamlett says.

Downloadable Content

The State of Youth Mental Health & Our Schools

How schools are responding to the rising demand for student mental health services.

.svg)

.png)